As I sat contemplating what fun, cool, interesting thing I would write for E/lectrify this week, I realized I was completely burned out on the whole data center/electricity demand growth thing. I have been writing about it, almost nonstop, for the past year because demand growth is already raising our electric bills and could soon affect whether our utilities and grid operators have enough power to keep the lights on.

At least that is the story reporters, myself included, have been telling to make what might elsewise be a highly technical and increasingly political story accessible to general readers — something they might want to know and care about.

But — during a recent morning scroll through LinkedIn — I tripped over a new study that forced me to look at the issue from a different angle and examine my own biases, which is kind of cool and interesting and a core responsibility of any good energy reporter.

The article in question — “Who do we trust on climate change, and why?” — was produced by researchers at the University of Queensland in Australia and the Edelman Trust Institute, a global communications firm that helps companies promote trust in their brands. The report focuses not only on who people trust for information about climate change, but why — the particular attributes that make a person or institution trustworthy.

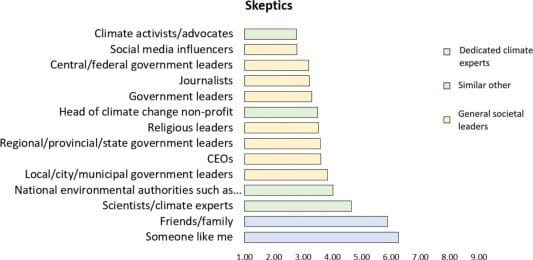

It also charts the differences in trust between those the study terms as believing in climate change and those the researchers define as climate skeptics.

What is particularly cool about this study is that it is based on an online survey of 6,479 people in 13 countries across all geographic regions, and climate believers outweighed the skeptics by about 11 to one. What’s more, the researchers found that the most trusted sources for both believers and skeptics were — in slightly different order — scientists and climate experts, friends and family, and people they identify as like themselves.

Figure 1: Sources of trust for climate believers

For believers, scientists and climate experts came first, followed by “someone like me” and friends and family, while skeptics put scientists and climate experts third, behind people like themselves and friends and family. (See Figures 1 and 2.)

Similarly — and definitely cool — both groups rated social media influencers and various government officials as among the least trusted. Journalists earned a medium ranking from the believers, and a low ranking from the skeptics — fourth from the bottom, behind government officials.

Figure 2: Sources of trust for climate skeptics

For me, the fact that people around the world trust friends, family members and people like themselves as primary sources for information on climate change was a bit unsettling. I tried to imagine social events or dinner table conversations where the topic was discussed thoughtfully and in depth. (With other green geeks, yes; with family members, highly unlikely.)

From there, it wasn’t a big leap for me to go from who do we trust for information on climate change to — wait a minute, who do we trust for information on data centers and demand growth? How do we evaluate their trustworthiness?

We are at a pivotal moment in the evolution of U.S. and global energy systems. Demand for energy and the technologies available to meet that demand are changing at an unprecedented speed and scale.

Decisions are being made today that could determine how we prepare for and respond to these changes — how we produce and consume electricity, and how much we pay for it — for years to come.

And those decisions — how they are made and how we understand them — will depend on information we receive from people and organizations we may or may not consider to be trustworthy.

Will the data centers show up?

Translating climate change trust into data center/demand growth trust is a little tricky, first because information about climate change has been available from a range of sources for decades, giving people time to think about who they do and don’t trust and why.

While it’s a well-established matter of panic and obsession within the energy industry, demand growth is still a relatively new issue, and the relevant information is, at best, fluid. Estimates of just how much power we’re going to need in the next five to 10 years continue to shift upward, but are still speculative.

Will the data centers and their voracious appetite for electric power actually show up?

We also have little hard data on potential impacts and how different technologies may or may not meet growing demand. The ever-increasing number of studies available are based on computer-generated scenarios developed by utilities, grid operators, industry consultants or academics and can be interpreted in different ways depending on who’s looking at them.

So, who are our experts? Who are the people like us? Do we have believers and skeptics? Is there any one individual or organization that I could tell a friend or family member, “Yes, you can absolutely trust what they say”?

Answering these questions is where personal bias begins to surface. After writing about energy for 20 years, I tend to view the industry not in terms of adversarial relationships – good guys versus bad guys, consumers versus corporations – but vested interests.

I trust utilities insofar as I know they are truly dedicated to providing safe, reliable electricity to all their customers. But I also know that the major corporate utilities with the most political power are highly averse to technical and financial risk and prioritize shareholder profits.

Many of them are backtracking on net-zero pledges and developing plans for new natural gas plants, all in the name of reliability and meeting demand growth. They speak of affordability while asking regulators to allow them to charge their customers for new power plants or grid expansions before they come online, which means consumers could end up paying for cancelled projects.

Similarly, we are relying on grid operators — such as PJM Interconnection — to come up with plans for grid expansion to meet rising power demand when their years of foot-dragging and resistance to grid modernization are a major cause of current problems. They are fast-tracking their permitting processes to get new nuclear and natural gas plants online while hundreds of gigawatts of wind, solar and storage have been waiting for years.

On the political front, the current administration has intensely vested interests in promoting fossil fuels and nuclear energy, attacking renewables and expanding its own executive power, regardless of legality. Any information coming from the White House, the Department of Energy or other relevant federal agencies needs to be evaluated accordingly.

It is worth noting here that test queries to Google AI and ChatGPT suggested that federal agencies and industry regulators and analysts may be the most trustworthy sources of information on data centers and demand growth. ChatGPT does provide a more comprehensive and wide-ranging list of resources, such as the Uptime Institute, The Green Grid and Data Center Knowledge.

The flexibility debate

So, do most sources of information on data centers and demand growth come with implicit biases that may make them more or less trustworthy? Probably.

A key example right now is the debate around grid and data center flexibility as one approach to meeting demand growth. On one side are flexibility believers, who argue that if data centers would briefly decrease the amount of power they use, it would relieve stress on the grid at times of high demand, while also opening up space for new generation.

A much-cited study from Duke University suggested that if data centers curbed their power use by one quarter of one percent, 76 gigawatts of new power could be brought online.

Meanwhile, flexibility skeptics counter that such studies are not realistic or practical. Artificial intelligence data centers must run full bore, 24-7, they say, and the companies that own them — like Google, Meta, Amazon and Microsoft — won’t put their operations or profits at risk to provide such flexibility.

The believers tend to see solar, wind and storage as cleaner, more flexible power, which is also cheaper and faster to build. The skeptics may be more likely to see fossil fuels and nuclear as more reliable, 24-7 sources of electricity and advocate for streamlined permitting and a rollback in environmental standards to get such projects online as quickly as possible.

With system reliability and ever-rising utility bills at stake — not to mention national security and the AI race with China — who should we trust?

Figure 3: Attributes of trustworthiness for climate believers and skeptics

Here is where the attributes of trustworthiness come in (see Figure 3). In the climate change study, people evaluated the trustworthiness of information based on its use of supporting data and research, and whether it is easily understandable and not dismissive of opposing views — all top concerns for both believers and skeptics. Another core benchmark is whether a person or institution would profit from the information.

Believers and skeptics differed on other trust attributes such as academic credentials, shared goals and values, and passionate presentation — all significantly more important for believers than skeptics.

Are we asking the right questions?

I have been sitting with myself as I write this, asking myself, how trustworthy has media coverage of this issue been in general? How trustworthy have I been?

In the interests of full disclosure, I would classify myself as a qualified flexibility believer. As I have written elsewhere, while it is technically possible for data centers to flex their power use, it is not an immediate or silver-bullet solution. More study and demonstration projects likely will be needed to determine whether and to what extent it is viable, efficient and cost-effective.

I can check all the boxes on data-supported, easy to understand, and not directly profiting, and if you subscribe to E/lectrify and are reading this, you know I am passionate about the clean energy transition and at least hope that we share some views and values.

My one failing is that I can be less than tolerant of some opposing views, specifically those that completely discount renewables or fail to recognize that the data center/demand growth debate is directly linked to climate change.

If I hope to build trust with the broad audience of readers I would like to reach, I will have to challenge myself to keep an open and respectful mind.

The problem here is that the speed and scale of data center and demand growth are upending the careful and much slower pace of utility and grid planning and regulation, and trust does not move at digital speed; it is developed and earned over time.

Further, as the climate change study shows, trust is based as much on who we know — friends, family and others like ourselves — as what we know — science and data. How AI and its lightning-fast production of information might influence the balance here is uncertain but potentially significant.

I am beginning to wonder if we are even asking the right questions.

Insofar as data centers and demand growth are new and unprecedented problems, the most trustworthy solutions are likely to be new and unprecedented, which perhaps will mean developing more expansive and flexible definitions of trust.

The sources of information I trust most are those that offer fresh vision and inspiration — science-based, of course, but also asking new questions, challenging conventional wisdom and embracing risk and uncertainty.