If you wanted to know how many energy projects of various kinds — solar, wind, energy storage and natural gas — are waiting to get connected to the electric power system in the United States, the first thing you might do is a fast Google on “Berkeley Lab” and “Queued Up.”

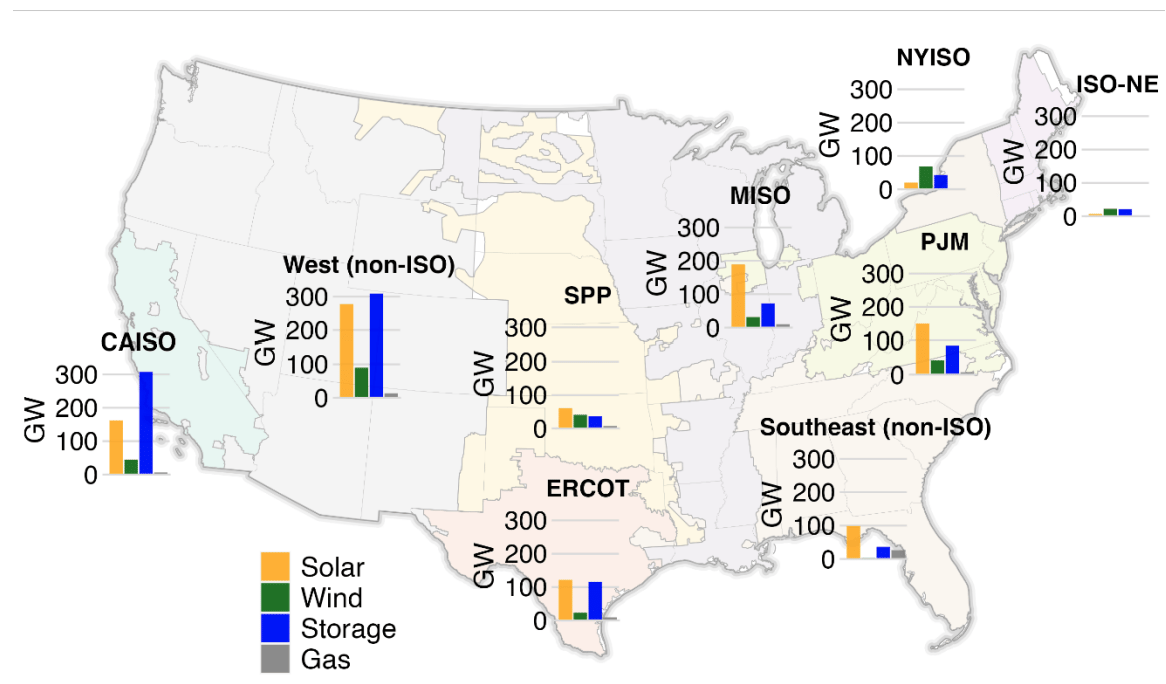

What you’d find, at the top of your search results, is a link to the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s authoritative annual report breaking down our country’s backed-up pipeline of projects by technology type and region (see map above).

In industry speak, these regional waiting lists are called “interconnection queues,” hence the title of the Berkeley Lab’s report, which, for green geeks like me, is a basic text with highly quotable figures.

One of my favorites: At the end of 2023, the U.S. had about twice as much power — 2,600 gigawatts (GW) — waiting to get online as the 1,300 GW that were then on the grid, generating power. More to the point, most of those queued-up projects were solar, wind and storage, with a smattering of natural gas.

I recently quoted these facts and figures to a member of the U.S. Congress, who was momentarily dumbfounded by them. (It was at an off-the-record event, so I can’t name names.)

The last edition of Queued Up came out in April 2024; so, I have been wondering when or even if we might see a 2025 update, given the Trump administration’s campaign to quash any programs or research related to renewable energy.

I reached out to contacts at the Berkeley Lab (who shall also remain nameless for obvious reasons), who told me that a draft of Queued Up 2025 is indeed in existence and was sent to the Department of Energy for review.

Its current status or when it might be published is unknown, and DOE has not acknowledged or answered any of my emails asking for an update.

In the interim, however, the Berkeley Lab folks directed me to interconnection.fyi, a very cool website set up by enterprising data nerds, Chris Talley and Steven Zhang, to provide instantly accessible detail on the power generation waiting to connect to the grid.

Shrinking queues

Why this is important — why anyone might care about how much power has been waiting to connect to the grid, in some cases for years — is the “energy emergency” that, according to our president and his supporters, could soon leave us all powerless and in the dark.

True, electricity demand is on the rise, and accelerating fast, due to artificial intelligence data centers’ voracious appetite for electrons, along with building and transportation electrification. But Trump et al. are arguing that a surge in fossil fuel generation – primarily from natural gas – will be needed to ensure adequate, reliable power and save the country from rolling blackouts.

By most estimates, building all these new power plants and getting them connected to the grid will take about five years.

Federal and regional efforts, slow and incremental, are underway to restructure grid planning and permitting. But the kneejerk response to rising demand has been to allow new natural gas and nuclear plants and some storage to connect to the grid ahead of the hundreds of gigawatts of solar, wind and more storage that have been waiting years to get online.

I will not, at this time, even try to explain the administrative and political mismanagement and lack of vision and planning that lie at the root of the current tangled situation, or just how complicated it is to get permission to connect a project to the grid.

In grossly oversimplified terms, the organizations that determine which projects can go online allowed their interconnection queues to get so backed up that, in some cases, they stopped accepting new projects for a year or more. (I will be providing a more detailed explanation in a future Energy Literacy post.)

Which brings me back to interconnection.fyi, which in the absence of the Berkeley Lab report, has just released its own analysis of the current state of the interconnection queues, showing the total backlog waiting to get online is shrinking for the first time in years.

This is big news, and the main driver, Talley and Zhang say, is the initial impact of queue reform. Regional grid operators have added new requirements for projects applying to get online — such as higher fees and specific project development milestones — that have pushed less-developed, or “speculative,” projects out of the line.

The report does not give a total figure for current capacity in the pipeline, but a chart on the interconnection.fyi website pegs it at about 2,000 GW – a 23% drop from the Berkeley Lab’s 2024 figures. The dropouts are wind, solar and storage projects, with solar taking the biggest hit (see chart below).

Natural gas is edging up, but is still well behind renewables.

You don’t have to be a geek

And why I am telling you this is because we are being told that natural gas and nuclear are the best answers to data centers’ booming electric power demand, when we clearly have other, even better options. The solar, wind and storage sitting in project pipelines across the U.S. are quicker and easier to build and can provide flexible, reliable power — something the clean power industry has been screaming from the rooftops for the past few months, to little avail.

Where frontal assault is not being effective, more nuanced arguments may be, which is why reports like Queued Up and interconnection.fyi’s analysis are vitally important.

You don’t have to be a geek to go on interconnection.fyi and play around with the charts, which provide different perspectives on the power waiting to get online, in different formats. It’s just cool, fun and easy to understand.

An interactive map breaks down current applications to connect to the grid by county. With one click, I found out Prince George’s County, Md., where I live, has five projects waiting to get online.

When I finish writing this, I’ll probably spend some time digging a little deeper to find out about these projects — what they are, where they are and their potential impact on power reliability, affordability and carbon emissions.

Talley and Zhang see the projects waiting to go online as “a story of American resourcefulness, regional pride and shared ambition. Each project is a local response to a national challenge, contributing a thread to the energy tapestry we're building together. From sun-soaked deserts to wind-swept plains, we're not just reshaping the grid — we're collectively preparing for an electric and uncharted future.”

Hopefully, DOE will release Queued Up 2025 soon and without any ideological edits, omissions or rewrites, adding to the basic understanding of our electric power system that we all need.

For example, it is worth noting that the two states that have faced real energy emergencies in recent years – California (wildfires) and Texas (winter storm Uri) – responded by putting more solar and storage online. In both cases, the quickly deployed, flexible power allowed both to ride out subsequent extreme weather events.

After I gave the federal lawmaker the numbers from the Berkeley Lab’s 2024 report, I asked this person, as innocently as possible — “If these renewable projects are ready to go, shouldn’t we get them online first?”

The answer was a nod and a hesitant but clearly audible “yes.”