Editorial note: Due to an overstuffed calendar, I did not send out an E/lectrify email last week, and this week, I will be taking off for Thanksgiving, so the following story is doing double duty, catching up and keeping everyone E/lectrified for the holiday. Best wishes to all.

A couple weeks back, I wrote an E/lectrify post about the five or six things folks need to know about utility commissions, in which I urged my readers to spend five minutes a week checking out their utility commission’s website, to look at calendars and meeting agendas.

The goal was to pique everyone’s interest in knowing more about their commissions and possibly getting involved in issues that are important to them. Also, when you dig into meeting agendas or other documents, you can discover or uncover all kinds of things you didn’t know were going on and you have some major questions about.

Which is what happened to me the morning of Nov. 17, when I took a look at the Maryland Public Service Commission’s Nov. 19 meeting agenda.

I live in Maryland, and before I wrote the above-mentioned post, I was not following my own recommendation; quite the contrary. So, I decided that from now on I would begin my week with my own five minutes on the PSC website. It’s on my calendar, on indefinite repeat, so I don’t forget.

Now, like many utility commissions’ agendas, the PSC’s starts with a “consent agenda,” which includes items the staff thinks are pretty straightforward and don’t require discussion, just a vote.

But the first item on the PSC’s consent agenda for Nov. 19 didn’t look particularly straightforward, at least not to me. It was an application from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Southeastern Power Administration to get a 48-year-old hydroelectric dam — the Laurel Dam — certified as a renewable energy facility under Maryland’s Renewable Portfolio Standard Program.

When I took a quick look at the application — downloadable from the agenda — I found out the Laurel Dam, pictured above, is a federal dam located in Corbin, Kentucky (where, pre-KFC, Col. Harland Sanders started serving fried chicken at a roadside restaurant in the 1930s). Built by the Army Corps of Engineers, the dam currently produces about 61 MW of power.

Corbin is in the southeast part of the state, about 500 miles from Maryland. So, why would the PSC certify a dam located there as a renewable energy facility for Maryland’s RPS — which they did by a unanimous voice vote without any discussion on Nov. 19.

An email from DOE’s Southeastern Power Authority informed me that all of the power from the Laurel Dam goes to the East Kentucky Power Cooperative, which asked DOE to submit the application to the PSC. According to the co-op’s website, it provides power to 16 smaller electric cooperatives serving more than one million customers across the state, so it is highly unlikely that any of the carbon-free electricity from the dam will get anywhere near Maryland.

The problem with RECs

Now, this story has a lot of moving parts, so let me first say that the PSC has done nothing illegal. The problem is with Maryland’s renewable portfolio standard, which at present requires utilities in the state to provide 52.5% of their power from renewable energy, including hydroelectric, by 2030. The interim benchmark for 2025 is 38%, according to a recent report from the state’s Department of Legislative Services.

But utilities don’t actually have to generate 38% of their electricity from solar, wind, geothermal or hydroelectric projects that provide power to Maryland, either directly or indirectly through PJM Interconnection, the regional grid operator. (The state imports 40% of its power from PJM.)

Rather, Maryland utilities only have to buy enough renewable energy certificates, or RECs, to meet their annual RPS targets. RECs were developed as a way to certify that renewable energy is being produced by a specific facility – one REC equals one megawatt-hour of carbon-free power.

Things get a bit wonky here because there are two kinds of RECs — bundled and unbundled — and the RECs I am talking about here are unbundled, which means they are sold separately from the renewable energy project that produced them. In essence, the buyer gets credit for clean energy without generating or buying it.

Bundled RECs stay with the project that produced them — a package deal. (A good, not too weedy explanation of bundled versus unbundled RECs can be found on the Retail Energy Advancement League website here.)

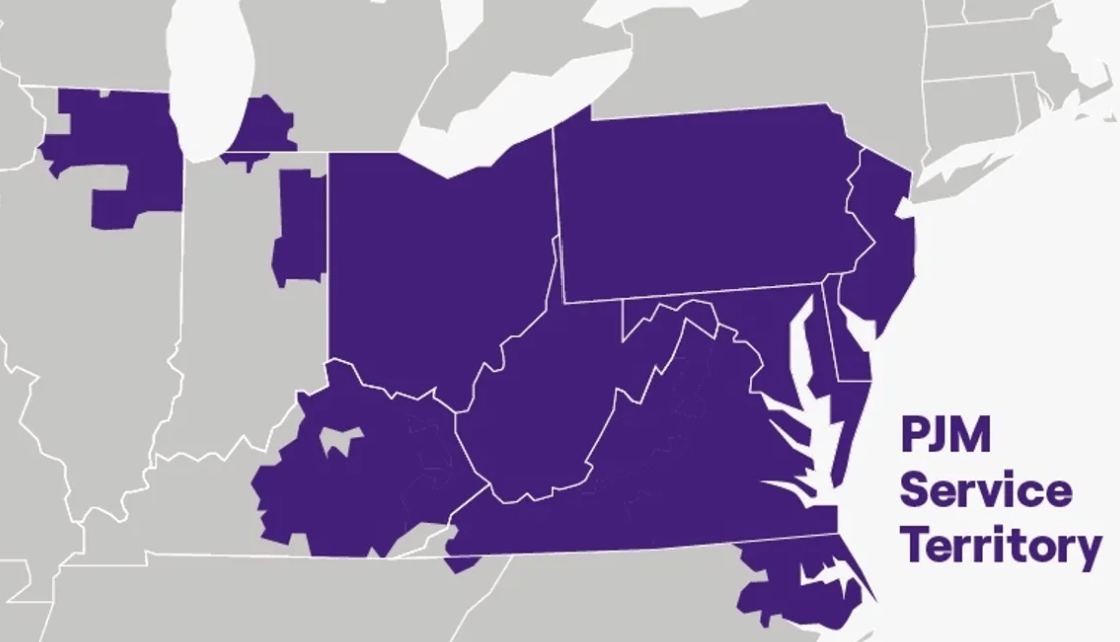

In Maryland, unbundled RECs can come from projects located either in the state or anywhere in PJM’s service territory, which includes 12 other Mid-Atlantic or Midwestern states and Washington, D.C., or even in any states adjacent to a PJM state. The eastern half of Kentucky, including Corbin, is in PJM. (See map below.)

Maryland’s RPS allows RECs from all PJM and PJM-adjacent states. (Source: Canary Media)

And here is why I am telling you all this. In theory, RECs — bundled or unbundled — are supposed to promote the deployment of new renewable energy projects or other clean technologies, which sometimes does happen.

Washington, D.C. has some of the highest REC prices in the country — $400 or more. So, city homeowners with rooftop solar can sell their RECs and channel the profits to further home electrification, for example, buying an induction stove or heat pump. REC sales have also helped fund D.C.’s Solar For All program, which has cut utility bills in half for thousands of low-income residents across the city (which I wrote about here.)

But in Maryland, the RECs from the Laurel Dam likely will only be bought by a utility to meet the state’s RPS requirements, without adding any new solar, wind or other clean energy to their systems. Further, the cost of the RECs will be passed on to customers.

One example, renewables currently make up less than 7% of Baltimore Gas and Electric’s generation mix, according to the utility’s website, which means it is buying ginormous amounts of RECs to meet the state’s 38% interim RPS.

The REC shell game

Now why you might care about any of this is that Maryland is not an isolated case. Although RECs were created to promote the growth of renewables — to certify that utilities are meeting their states’ renewable targets — they have become a shell game.

The high-level argument for the use of unbundled RECs is that the clean energy produced in one location — Kentucky — will offset the greenhouse gas emissions produced by fossil-fueled power plants in another, like Maryland, hundreds of miles away. Emissions will be reduced or at least not increased — somewhere.

Instead, RECs are being sold and bought to allow utilities to circumvent their state’s renewable energy targets or to greenwash their ongoing reliance on fossil-fueled generation. Utilities that offer their customers “green power” programs are in some cases only buying RECs, rather than putting new clean power on the grid.

Any time a utility or other electric company offers you “clean power” at a premium price, your first question should be what are they actually selling — power from a recently constructed renewable energy project, preferably in or near your community or state, or RECs?

At present, 28 states and D.C. have some kind of renewable portfolio standard, which means utilities in those states could be buying unbundled RECs to meet their clean energy targets.

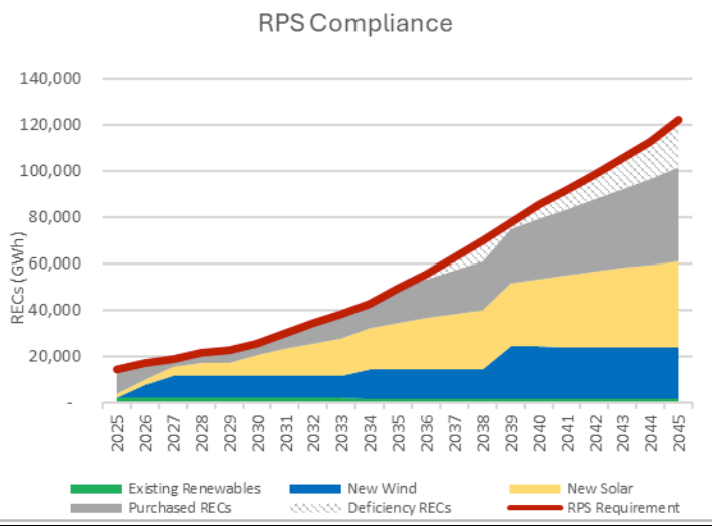

Virginia’s Clean Economy Act, passed in 2020, requires Dominion Energy, the state’s largest corporate utility, to supply 100% of its electricity from carbon-free sources by 2045. Yet, in its most recent plan for new generation, the utility estimates that in 2045, a third of its power will still come from natural gas, to be offset by the purchase of 40,000 to 60,000 gigawatt-hours of unbundled RECs (see chart below).

How Dominion Energy plans to meet Virginia’s 100% clean energy mandate.

REC sales have become an integral part of RPS compliance, as well as a lucrative business, with companies vying to help homeowners, businesses and renewable developers aggregate and sell their RECs.

At this point, completely prohibiting the use of unbundled RECs for RPS compliance seems highly unlikely, but states should at least set limits. In California, utilities can only buy unbundled RECs for 10% of their RPS requirements.

I did reach out to both DOE and EKPC to ask why they had applied to the Maryland PSC to get the Laurel Dam certified to sell RECs to the state’s utilities. EKPC told me that the co-op has sold RECs from the dam to utilities in other states, with the proceeds used “to keep costs affordable for all the owner-member cooperatives.”

It wanted the Maryland certification because the state “represents a promising market” — that is, utilities in the state will need to buy lots of unbundled RECs.

RPS vs. RECs

As I write this, the United Nations’ 30th Climate Change Conference of the Parties, aka COP30, has ended once again without nailing down any kind of international commitment or plan for the phaseout of fossil fuels. Meanwhile, President Trump is doing everything he can to keep U.S. coal and natural gas plants online, build more and open more federal land and coastal waters to oil and gas drilling.

States and cities are now the frontline of climate action and clean energy deployment in the United States, and their RPS targets continue to drive a significant amount of solar and wind development. State clean energy mandates added 16 GW of renewables to the U.S. grid in 2024, about 37% of new carbon-free capacity for the year, according to the latest figures from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

What we do not know is how much more might have been added if utilities were not allowed to buy unbundled RECs to meet their state goals.

It looks like Maryland will continue to certify existing projects to provide the state’s utilities with unbundled RECs, as opposed to ensuring new clean power is built. The PSC consent agenda for Nov. 25 includes an application from the 17-year-old Forward wind farm in Berlin, Pennsylvania.

The project generates about 47 GWh of power per year, or 47,000 RECs.

What are you finding on your utility commission’s website? Tell me your stories, and I’ll write about them in a future E/lectrify post.