Ilya Krasnoyarov has been working for commercial solar developers in Minnesota and analyzing utility bills from the state’s 175 electric utilities for the past eight years, and he has the spreadsheets to prove it.

“So, the first thing you [see] is an energy charge,” Krasnoyarov told me, during a recent online interview, where he shared a sample spreadsheet, scrolling across the more than 100 columns he had set up to track all the different line items of the various bills he had analyzed. “People think they pay 4 cents [per kilowatt-hour] … But then you add on the fuel rate, which is another 3 cents. So, now you doubled your rate, and people don’t understand they’re paying for fuel.”

If all that weren’t complicated enough, “each utility has a different way of doing math,” he said. “Is it a percentage? Is it fixed? Is it based on the energy charge? Does it include fuel? And they won’t tell [you]; you have to, like, do the math,” something most people don’t have the time, expertise or interest in doing.

My efforts to break the seemingly indecipherable code contained in our utility bills started with a post on LinkedIn, asking the online energy community to share their bills with me. The response was overwhelming. Krasnoyarov was one of the more than three dozen individuals who commented on the post, offering bills and insights.

My brother, Karl, who lives in Florida, sent his bill from Florida Power & Light, which simply breaks the charges into fuel and non-fuel components. Significantly, the non-fuel charges were more than three times the fuel charges, but both were based on the amount of electricity he and my sister-in-law Margrit use.

My friend Ted Tiffany in California sent me one of his Pacific Gas and Electric bills, showing a $60 credit he got for the power generated from his rooftop solar panels. He is also on one of PG&E’s time-of-use rates, which charge different amounts per kilowatt-hour for power used at different times of day.

TOU rates are designed to incentivize customers to use less power during more expensive “on-peak” hours — typically, late afternoon and early evening — by shifting their use to cheaper “off-peak” hours, early morning and late at night. My brother, on the other hand, is on what are called volumetric rates, which means the bill is based on how many kilowatt-hours of electricity a customer uses, regardless of the time of day.

If you go over a certain base amount per month — in this case, 1,000 kWh — you pay more for any electricity you use.

Simple = uninformative?

And that’s only a glimpse of how complicated and confusing electric bills can be. The conventional wisdom in the utility industry is that most consumers only look at their bills for about three to five minutes each month — as long as it takes to write a check or make an online payment — and they aren’t particularly interested in reading or understanding them.

Krasnoyarov put it this way — most people “just kind of accept” their electric bills. “They don’t have a choice,” he said. “They can’t combat it. They don’t even know if they used that energy. … Most people just don’t appreciate the complexity and meaning of all this on their day-to-day lives.”

This passive acceptance could be changing. Electricity demand and, with it, electric bills are going up. People are feeling the impact in their daily lives, and they want to understand what’s happening and what if anything they can do about it.

I’m not a spreadsheet kind of person, and tracking each and every charge across our country’s 3,000 some odd utilities would be mind-numbing, if not impossible. But, in addition to the utility bills shared with me, I have been talking with industry experts like Krasnoyarov and prowling around utility websites, looking at the annotated, sample bills most utilities have online for their customers.

The result is the first-ever E/lectrify Utility Bill Survey, looking at if and how U.S. utilities are providing their customers with full, clear and useful information on their energy bills to help them prepare for the price increases ahead.

What follows is entirely selective and by no means scientific or comprehensive, but I have tried to make it representative of the range of U.S. utilities and their bills. My goal is to provide an overview of the information customers may or may not see on their bills, along with basic explanations of the different categories of charges.

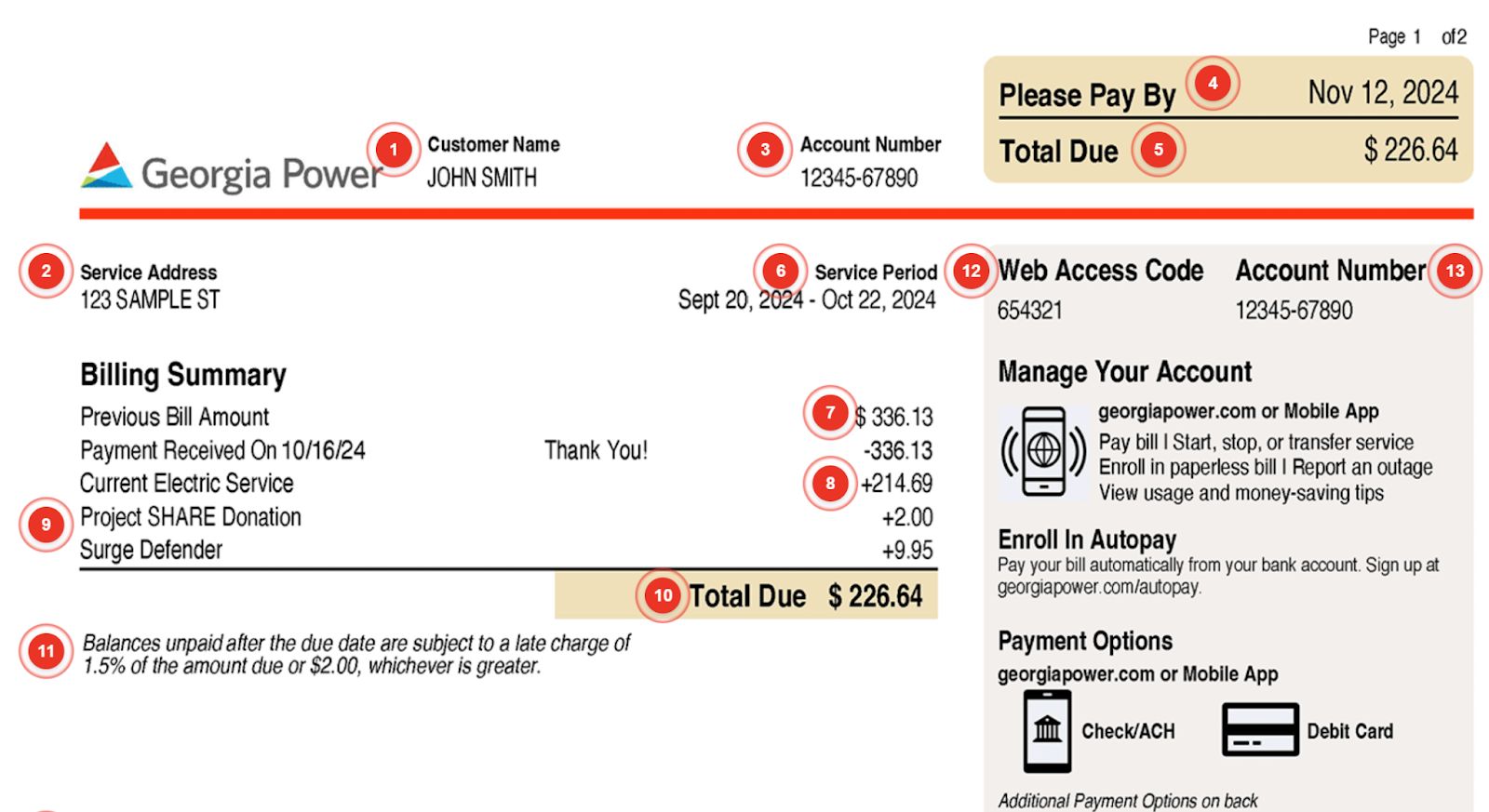

One of my first findings is that utilities with the simplest bills tend to provide the least information. The prime examples are a group of Southeastern utilities, including Duke Energy and Southern Company and its three subsidiary utilities — Georgia Power, Alabama Power and Mississippi Power.

Duke and the Southern Co. utilities are “vertically integrated,” which is industry jargon for companies that both produce electricity from their own power plants and deliver it to customers via their own network of poles, wires and other infrastructure. They are also in states where they have a virtual monopoly on providing electric service to consumers.

Thus, Georgia Power’s sample bill has a single line item — Current Electric Service — which covers “cost to generate and distribute electricity,” according to the explanation that pops up if you click on the numbered note on the online bill. But what Georgia Power and Southern’s other utilities don’t provide are the rates their customers are paying per kilowatt-hour, or how those rates are divided between the electricity itself and the delivery system.

Duke Energy’s bills are equally uninformative, providing only a monthly usage figure and energy charge.

How SMUD does it

So, what information should a utility bill provide to ensure consumers understand what they’re paying for?

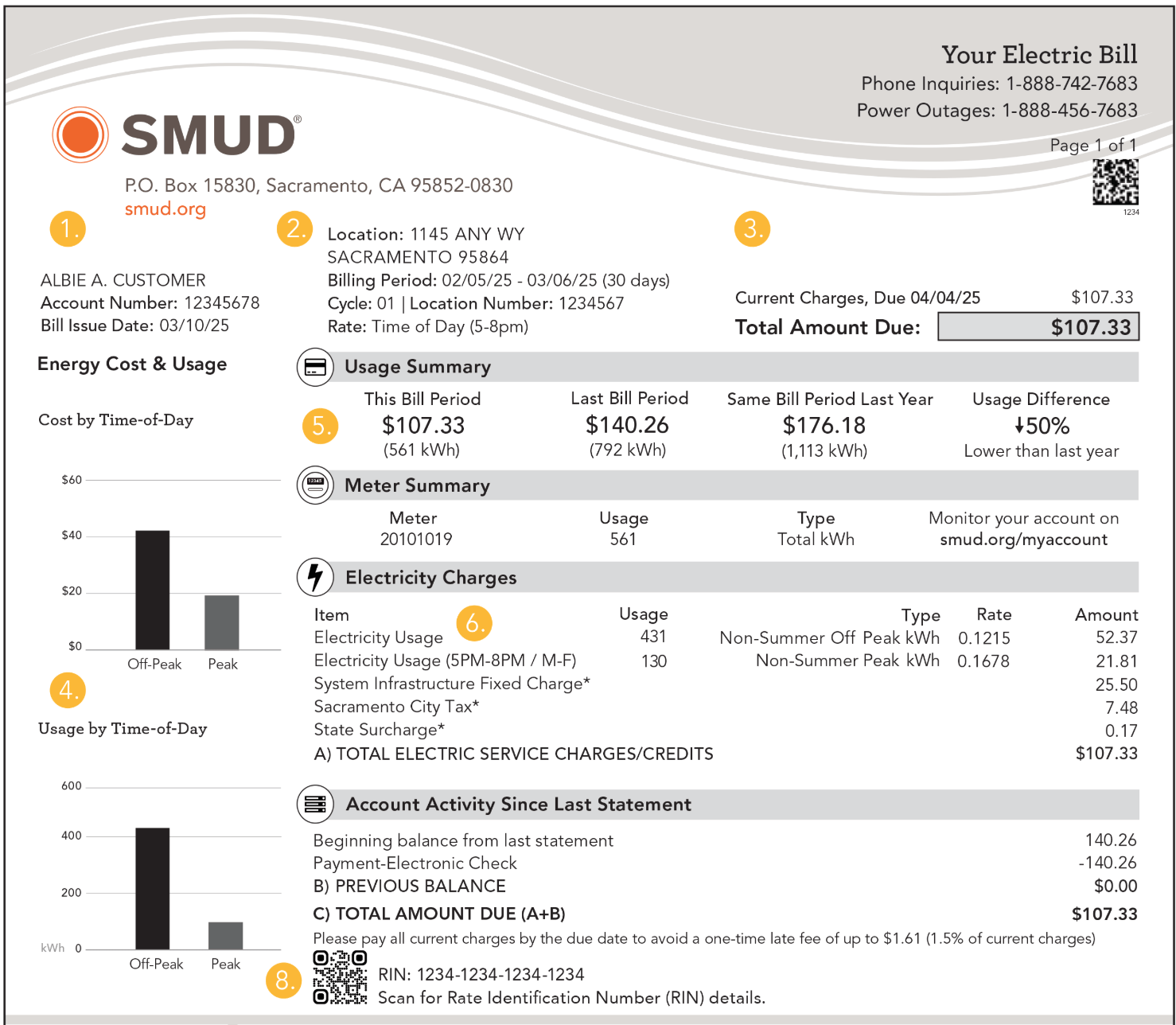

I am going to start with the Sacramento Municipal Utility District, aka SMUD, a California municipal utility known for its innovative policies and programs. Its Understanding Your Bill page contains a menu of bill formats, depending on a customer’s particular rate structure, ranging from a standard TOU rate (here called time of day, TOD) to rates for customers with solar and storage, feeding power back onto the grid.

Looking at the Standard TOD bill, what’s particularly cool is, first, the usage summary up top, comparing a customer’s bill for this month with their bill for the previous month and the same month last year, followed by the year-over-year difference.

Then, on the lefthand side, SMUD provides two charts tracking the customer’s’ on- and off-peak costs and usage, which are then broken down into per-kWh charges.

SMUD is vertically integrated, owning both generation and distribution, but unlike the Southeastern utilities, it breaks out its distribution costs via a fixed charge for system infrastructure. In other words, throughout the bill, customers get a clear picture of how much energy they’re using, when they’re using it and what they’re paying for it.

The Rate Identification Number, the small QR code at the bottom left, is a new and very cool feature coming to all California electric bills, mandated by the California Energy Commission. The RIN will link customers to a statewide data base of TOU rates, allowing them to get hourly information on their TOU rates and compare them with other utilities’ rates. The database is expected to go live in 2026 or 2027.

Unregulated line items

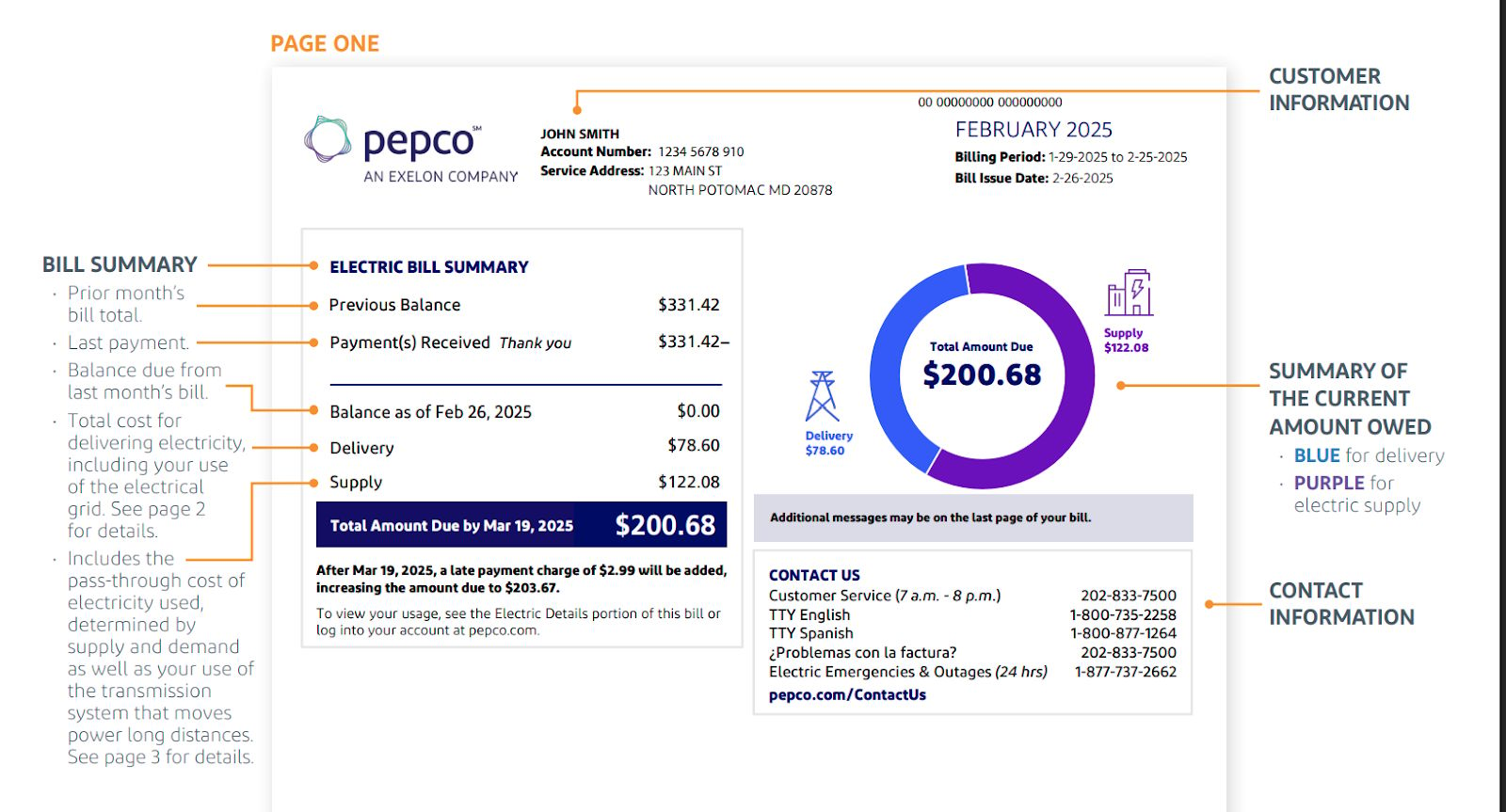

Bills get more complicated in states like Maryland, which have “unregulated” markets, meaning utilities here are not allowed to own generation and must compete with other retail power companies to provide electricity to consumers. So, utilities like Pepco — my utility — break down their bills into charges for supply (electricity used) and delivery (how it gets to your home), along with a bunch of jargony line items, which the sample bill does a middling job of defining.

The front page pie chart, summarizing supply and delivery charges, is eye-catching and useful, but too many of the line items included in the delivery charges (on the second page, not seen here) are lumped together as fixed costs.

I had an online sit-down with Katarzyna Dana, a senior manager for rates at Pepco, who patiently answered questions like why my bill has three different line items all labelled “Energy Charge” — including one as part of my delivery charges. She also had to untangle why the charge for maintaining the interstate transmission lines that deliver power to Maryland is in the supply portion of the bill, rather than in delivery.

The answers are pretty wonky, so I won’t go into them in detail here, but a lot of it has to do with Maryland being dependent on the regional grid operator, PJM Interconnection, for much of its power. One thing she did point out is that because Pepco doesn’t own generation, it only makes a profit on the delivery charges. The supply fees are basically all pass-throughs.

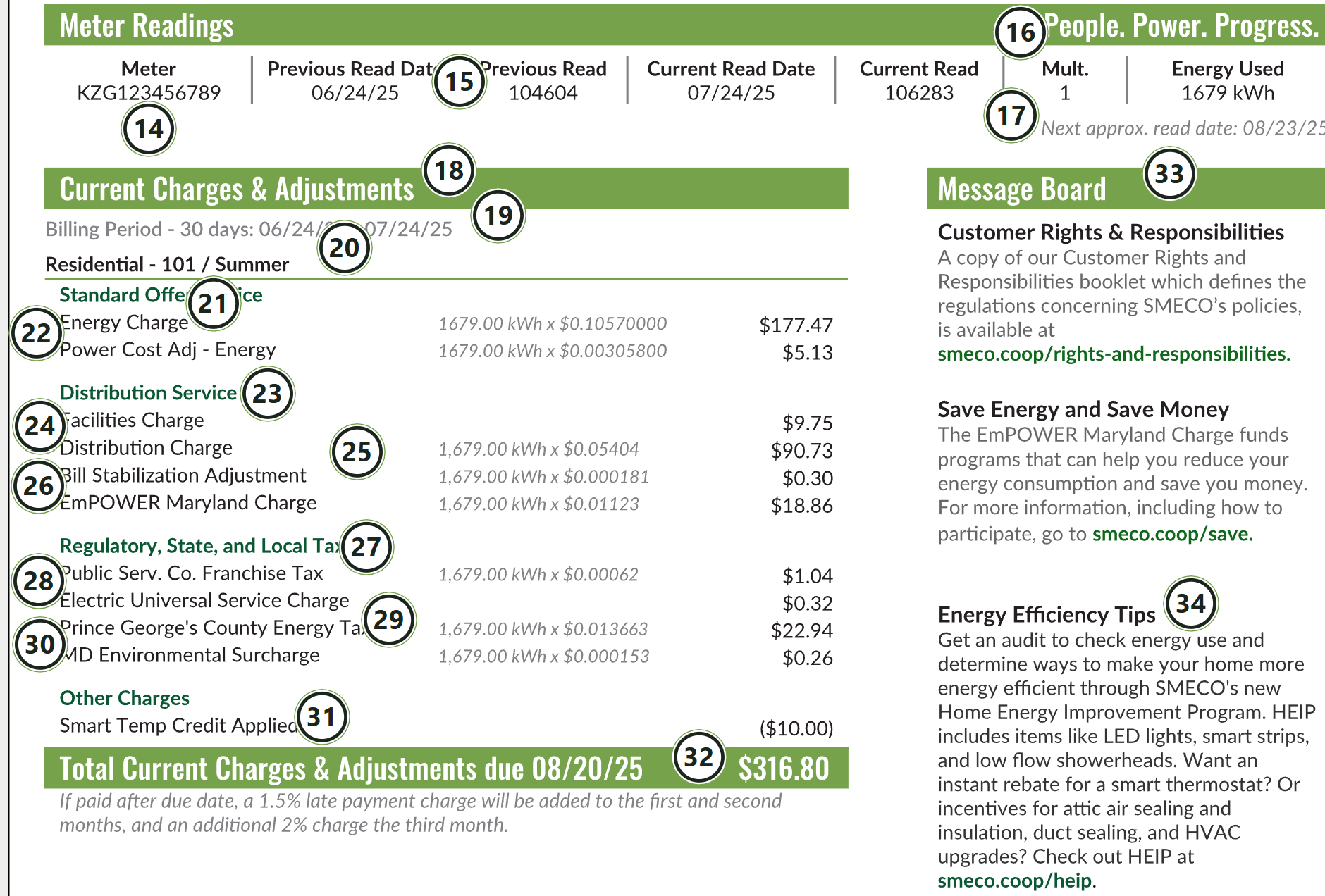

By comparison, the Southern Maryland Electric Cooperative has line items very similar to Pepco’s – broken down into supply and delivery categories. But the co-op’s sample bill is extensively annotated, with each line item explained in a numbered pop-up box. It is comprehensive and detailed, if a bit cluttered (See top of post.)

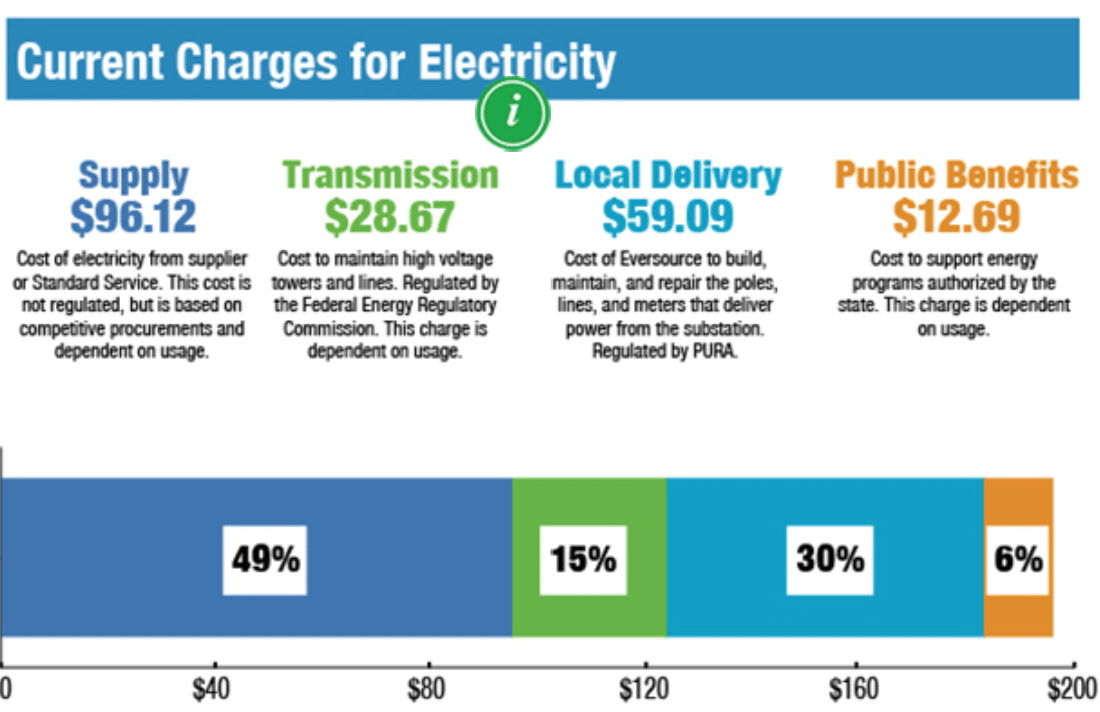

Looking at utility bills in other deregulated states, I was particularly impressed with Eversource’s sample bill in Connecticut. The utility breaks down a customer’s total cost into four key components – electricity supply, transmission, local delivery and public benefits – and provides appropriate definitions for each. (The image below is a detail from the larger bill.)

Texas has a bewildering number of charges that may or may not turn up on a customer’s bill. El Paso Electric, which is vertically integrated, has a cute cartoon video going over the basics and a lengthy list explaining other potential charges.

A brief word here on riders, which are additional charges utilities may tack onto their customers’ bills outside of their normal rate-setting process. Riders can pile up, padding out bills with extra or hidden charges.

Dominion Energy in Virginia, another of the Southeast’s monopoly utilities, is notorious for its use of riders, with between 11 and 15 separate riders potentially added to but not listed on its residential bills.

Questions for customer success

I have left many bills and line items unexplored here, but even this partial survey sends some clear messages.

Utilities have many different ways to present and explain critical information on their bills. Some are being thoughtful and creative about it; others remain stubbornly uninformative.

Consumers should expect, if not demand, that their electric bills contain full and clear information on their energy use and the various rates, taxes, riders and other fees they are being charged.

As electric bills go up – as they undoubtedly will – this information will be essential to help consumers make decisions about how to manage or change their energy use.

MCE – originally, Marin Clean Energy – is a community choice aggregator utility in Northern California, which has developed a “customer success” approach to educating its consumers.

Started in California, CCAs grew out of communities’ desire to get more of their electricity from clean sources, effectively opting out of the slower pace of transition and higher prices of the state’s major corporate utilities. Now 15 years old, MCE was the state’s first CCA and, according to Zae Perrin, vice president of customer operations, its standard energy mix is 63% renewable, with a Deep Green option providing 100% clean power.

MCE customers still get a bill from PG&E, which includes their MCE charges, leading to a good bit of confusion and lots of questions. So, Perrin said, the team in MCE’s in-house call center will spend as much time as necessary walking customers through their four-page bills and explaining the different charges.

For those concerned about rising bills, he has three questions. “The first thing is, when are you using your energy? The second is why and how, and the third is, what is your goal with those two things?

“Once you have those items, then you can have the true conversation of how that impacts your bill, and how much is that going to motivate change — for you as the consumer to change one, two or three or all.”

.